Best Management Practices

Use these tools to assess the risk of developing herbicide-resistant weeds and to manage fields with resistant weed populations.

By bringing diverse crop management techniques to their farms, growers can mitigate the development and spread of herbicide-resistant weeds. For more detailed information, download our Guideline to the Management of Herbicide Resistance document.

Background

Over the past decades, overreliance on herbicides for weed control has led to a reduction in the need for ‘traditional’ agronomic (non-chemical) strategies of weed control.

Cropping patterns have adapted, driven by the possibility to further increase crop output, to rely more and more on these products. Whilst economically this shift has been rewarding to farmers, some negative consequences have emerged which now need to be addressed in the interest of longer-term sustainability.

One result of modern agriculture and the reliance on herbicides is the emergence of populations of weeds which are resistant to products designed to control them. All natural weed populations regardless of the application of any weed killer probably contain individual plants (biotypes) which are resistant to herbicides. Repeated use of a herbicide will expose the weed population to a selection pressure which may lead to an increase in the number of surviving resistant individuals in the population. Consequently, the resistant weed population may be selected to the point that adequate weed control cannot be achieved by the application of that herbicide.

The first case of herbicide resistance in weeds was identified in 1964. Today, more than 270 resistant grass and broadleaf weed biotypes have been recorded across over 50 countries worldwide (Heap, 2025). Despite this seemingly dramatic development, no herbicides have been completely lost to agriculture. They remain - and will continue to be - an integral part of food, feed, and fiber production when used effectively in combination with sound agronomic practices. This integrated approach is known as Integrated Weed Management (IWM).

Definitions

Weed Resistance – Resistance is the naturally occurring inheritable ability of some weed biotypes within a given weed population to survive an herbicide treatment that would, under the use of the recommended rate and applied in the appropriate conditions, effectively control those biotypes. Selection of resistant weed biotypes may result in control failures.

Cross-Resistance – Cross-resistance exists when a weed population is resistant to two or more herbicides based on a single resistance mechanism.

Multiple-Resistance – Multiple-resistance exists when a weed population is resistant to two or more herbicides with different modes of action.

Resistance Mechanisms – The resistance mechanism refers to the method by which a resistant plant overcomes the effect of an herbicide. The mechanism present will influence the pattern of resistance, particularly to the cross-resistance profile and the dose response. Herbicide resistance mechanisms have been classified into two main groups, target-site resistance (TSR) and non-target site resistance (NTSR).

Target-site resistance (TSR) – It occurs when changes in a weed biotype reduce the binding affinity between an herbicide and its target. Changes may be an altered target site or amplification of the target gene, which leads to overexpression of the target enzyme, limiting herbicide phytotoxicity. Mixture and/or rotation of herbicides targeting different sites of action are effective strategies to manage TSR.

Non-target site resistance (NTSR) – It occurs when changes in a weed biotype reduce the amount of active herbicide reaching the target site. Changes may be reduced retention, absorption, and/ or translocation, enhanced metabolism (herbicide detoxification), and/or subcellular herbicide sequestration. The presence of such a mechanism can complicates the selection of alternative herbicides to control weed biotypes with NTSR. It is for this reason that management strategies must incorporate more than simply a switch of product and should be reviewed by knowledgeable advisors.

Herbicide Mode of Action (MoA) – The overall interaction of an herbicide with essential processes within the plant.

Herbicide Site of Action (SoA) – The specific binding site, e.g., an enzyme, affected by a herbicide. The binding site is also referred to as target site.

The latest Mode of Action Classification Poster was released in 2024 by HRAC Global. The MoA Poster numbers each group of herbicides under the same MoA and SoA for ease of reference. The HRAC MoA Classification Poster can be downloaded here. Every second year, HRAC plans to update the poster.

The process of selection for herbicide resistance

In any field population, it is assumed that a small number of plants within a weed population is genetically different and contains the resistance trait to a given herbicide. The repeated application of that herbicide or any other with the same SoA will allow these plants (biotypes at population level) to survive and set seed. Over a period of several such ‘selection rounds’ the resistant biotypes can dominate the sensitive weed population.

This process is shown diagrammatically below:

Resistance risk assessment

How does a farmer establish that an herbicide resistance problem is developing or if his farming practices may lead to resistance appearing?

There are several factors to consider when evaluating herbicide resistance risk. Some of these relate to the biology of the weed species in question, others relate to particular farming practices.

Some examples are given below:

Biology and genetic makeup of the weed species in question

Number or density of weeds: As resistant plants are assumed to be present in all natural weed populations, the higher the density of weeds, the higher the chance that some resistant individuals will be present.

Natural frequency of resistant plants in the population: Some weed species have a higher propensity toward resistance development; this relates to genetic diversity within the species and, in practical terms, refers to the frequency of resistant individuals within the natural population.

Biological factors that influence the level of genetic variability within the weed population:

Reproduction Mode: sexual reproduction involves genetic recombination and introduces genetic variability in the offspring. As a result, weed populations that reproduce sexually tend to be more genetically diverse than those that reproduce vegetatively. Mating System: In sexually reproducing species, fertilization can occur via self-pollination or cross-pollination. Outcrossing species generally exhibit greater genetic variability, which can accelerate resistance evolution.

Sexual System: The distribution of pollen and ovules within flowers and plants influences mating patterns, adding another layer of variability that may favor resistance development.

• Monoecious: individual plants bear both male and female flowers, enabling self-pollination and some cross-pollination.

• Dioecious: male and female flowers occur on separate plants, which enforces outcrossing and increases genetic variability.

Seed Production Potential: weed species capable of producing large numbers of seeds per plant increase the likelihood of individuals carrying herbicide resistance traits being present in the field and subsequently selected under herbicide pressure. High seed output also creates more opportunities for genetic recombination, resulting in greater genetic variability within the population. When combined with high genetic diversity -particularly in dioecious or outcrossing species - this accelerates resistance evolution, as the variability carried through seeds represents an increased risk for resistance traits to be selected and spread.

Crop management practices which may favor resistance development:

Frequent use of herbicides with a similar site of action: The combination of ‘frequent use’ and ‘similar site of action’ is one of the most important factors in the development of herbicide resistance. Cropping rotations with reliance primarily on herbicides for weed ontrol: The crop rotation is important in that it will determine the frequency and type of herbicide able to be applied. It is also the major factor in the selection of non-chemical weed control options. Additionally, the cropping period for the various crops will have a strong impact on the present weed flora.

Lack of non-chemical weed control practices: Cultural or non-chemical weed control techniques, incorporated into an integrated approach, are essential to mitigate resistance evolution and increase the sustainability of the crop management system.

Table 1: Basic Assessment of the Risk of Resistance Development per Target Species

*Cultural control can be by using cover crops, differentiated sowing dates, stubble burning, competitive crops, stale seedbeds, no- or minimum-tillage systems, etc.

Risk of Resistance

| MANAGEMENT OPTION | LOW RISK | MODERATE RISK | HIGH RISK |

|---|---|---|---|

| Herbicide mix or rotation in cropping system | > 2 modes of action | 2 modes of action | 1 mode of action |

| Weed control in cropping system | Cultural*, mechanical and chemical | Cultural and chemical | Chemical only |

| Use of same site of action per season | Once | More than once | Many times |

| Cropping system | Full rotation | Limited rotation | No rotation |

| Resistance status to site of action | Unknown | Limited | Known |

| Weed infestation | Low | Moderate | High |

| Control in last three years | Good | Declining | Poor |

Table 1 provides a basic checklist of the major risk factors within a cropping system and ranks these as ‘low’, medium’, or ‘high’ risk of resistance development.

The checklist is to be used per weed species where a ‘Cropping System’ in its simplest form is the management of crop production in an individual field.

Failure to achieve expected weed control levels does not in most cases mean that a farmer has resistance. A full analysis of the herbicide application, rate of use, weed type and stage of growth, climatic conditions and agronomic practices should be reviewed with a knowledgeable advisor.

If, after the initial investigation, resistance is still suspected, then consideration of historical information may point to factors leading to resistance development. The following questions are recommended:

- Has the same herbicide or herbicides with the same site of action been used in the same field or in the general area for several years

- Has the uncontrolled species been successfully controlled in the past by the herbicide in question or by the current treatment?

- Has a decline in control been noticed in recent years?

- Are there known cases of resistant weeds in adjacent fields, farms, roadsides, etc?

- Is the level of weed control generally good on the other susceptible species except the ones not controlled?

If the answer to any of these questions is ‘yes’ and all other factors have been ruled out, then resistance should be strongly suspected. Steps should then be taken to leave a small area to collect a sample of whole plant or seed from the suspected resistant weed population for a resistance confirmation test.

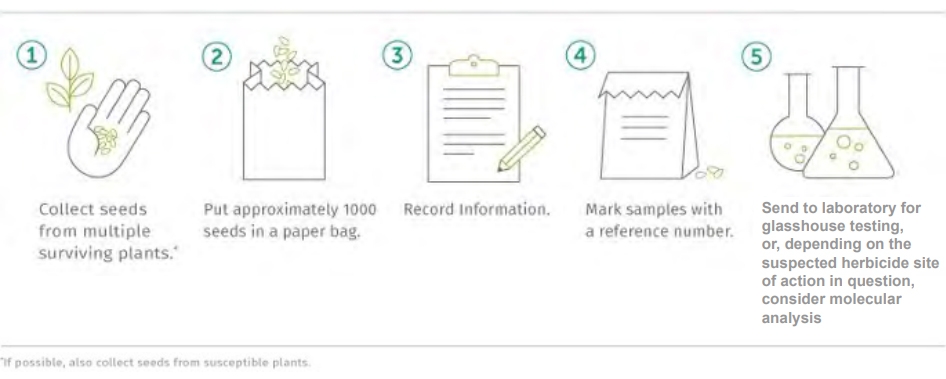

Seed Sample from Suspect Plant:

Guidelines for the prevention and management of herbicide resistance

The prevention of resistance occurring is an easier and cheaper option than managing a confirmed resistance situation.

Experience has shown that simply changing herbicides is not enough to overcome resistance in the mid- to long-term and that a sustainable, integrated system needs to be developed which is appropriate for the farm in question.

Integrated Weed Management is defined as the use of a range of weed control techniques, embracing physical, cultural, chemical and biological methods in an integrated fashion without excessive reliance on any one method (Powles and Matthews, 1992). The final goal is to introduce the highest possible diversity in the crop system.

The following information outlines the three key areas of weed management: crop management, cultural techniques and chemical tools which, when employed in a rotational and integrated approach will help to reduce the selection pressure on any weed species – hence significantly reducing the chance of survival of resistant weeds.

Rotation of Crops

The principle of crop rotation as a resistance management tool is to avoid successive crops in the same field which require herbicides with the same site of action for the control of the same weed species.

Crop rotation allows the following options:

- Different crops will allow rotation of herbicides having a different site of action.

- The growth season of the weed can be avoided or disrupted. Alternating winter crops with spring crops is essential.

- Crops with differing sowing times and different seedbed preparation can lead to a variety of cultural techniques being employed to manage a particular weed problem.

- Crops also differ in their inherent competitiveness against weeds. A highly competitive crop will have a better chance to restrict weed seed production.

Non-Chemical Techniques

Non-chemical weed control methods do not exert chemical selection pressure and assist greatly in reducing the soil seed bank. Non-chemical techniques must be incorporated into the general agronomy of the crop and other weed control strategies. Not all the examples given are adequate in all situations.

Some of the non-chemical measures for weed control could include:

- cultivation or ploughing prior to sowing to control emerged plants and to bury non-germinated seed delaying planting so that initial weed flushes can be controlled with a non-selective herbicide

- using certified crop seed free of weed

- post-harvest grazing, where practical

- stubble burning, where allowed, can limit weed seed fertility

- in extreme cases of confirmed resistance, fields can be cut for hay or silage to prevent weed seed set.

Modern Integrated Weed Management increasingly incorporates precision technologies that allow for spatially and temporally targeted interventions. Site-specific weed management systems, powered by advanced sensor technologies such as 3D cameras, multispectral imaging, and AI-based weed classification, enable tailored chemical and mechanical treatments. These innovations support data-driven decision-making and automation in spraying and hoeing operations, enhancing both ecological sustainability and economic efficiency. As these tools become more accessible, they are reshaping how physical, chemical, and cultural control measures are integrated within IWM strategies.

Herbicide rotation and herbicide mixtures

Herbicide rotation or mixtures refers to the rotation or mixtures of herbicide site of action against any identified weed species. HRAC has released a classification of herbicides according to mode of action (here). When planning a weed control program, products should be chosen from different modes of action to control the same weed either in successive applications or in mixtures. V. Guidelines for the prevention and management of herbicide resistance VI. Herbicide rotation and herbicide mixtures.

A general guideline for the rotation of chemical groups should consider:

- avoid continued use of the same herbicide or herbicides having the same site of action in the same field, unless it is integrated with other weed control practices

- limit the number of applications of a single herbicide or herbicides having the same site of action in a single growing season

- where possible, use mixtures or sequential treatments of herbicides having different sites of action but which are active on the same target weeds

- combine the use of pre- and post-emergence herbicides

- use non-selective herbicides to control early flushes of weeds (prior to crop emergence) and/or weed escapes.

From experience, we can conclude that rotation of herbicides alone is not enough to prevent the development of resistance. To retain these valuable tools, the chemical rotation explained must be employed in association with at least some of the other weed control measures outlined. In cases where metabolic resistance is already present, the herbicide site of action may not be the most relevant factor. Instead, the mechanism of degradation becomes critical, as it can span across different sites of action and chemical groups. Currently, there is no classification system for herbicides based on degradation mechanisms. Such cases need to be assessed individually by knowledgeable advisors.

The Use of Chemical Mixtures to Prevent Resistance

Mixtures can be a useful tool in managing or preventing the establishment of resistant weeds. For chemical mixtures to be effective, they should:

- include active ingredients which both give high levels of control of the target weed; and,

- include active ingredients from different sites of action.

The HRAC classification system organizes herbicides according to their sites of action, but it is not intended as a recommendation of which herbicide to use. This system is based solely on the chemical site of action and does not take resistance risk into account. Its purpose is to serve as a tool for planning herbicides mixtures or rotations by selecting products from different sites of action. This approach supports the development of effective strategies within an integrated weed management system.

Additional to the above guidelines, the grower should:

- know which weeds infest his field or non- crop area and where possible, tailor his weed control program according to weed densities and/or economic thresholds

- follow label use instructions carefully; this especially includes recommended use rates and application timing for the weeds to be controlled

- routinely monitor results of herbicide applications, being aware of any trends or changes in the weed populations present

- maintain detailed field records so that cropping and herbicide history is known

HRAC site of action classification

Classification of Herbicides According to Site of Action

The Global Classification Lookup tool can be assessed here.

What to do in cases of confirmed herbicide resistance

In cases where a control failure has been confirmed as resistant, immediate action is required to limit further seed production of the resistant plants.

The degree of the action will depend on the stage of the crop in the field and the extent of the problem.

Some options to consider:

- Eradicate the remaining weed population if growing in patches in order to limit build-up of the soil weed seedbank.

- Limit the field-to-field movement of resistant populations by cleaning planting, cultivation and harvesting equipment to avoid transfer of resistant weed seed

- Avoid using herbicide to which resistance has been confirmed unless used in conjunction with herbicides having a different site of action, active on the resistant weed population

- If the resistant population is widespread, consider grazing the crop or cutting for feed - being careful not to transfer resistant seed via manure

- Select these fields for rotation or set aside for the following cropping season

- Seek advice to assist in the long-term planning of weed control in these fields

Once resistant weed numbers are at a controllable level, implementation of an integrated weed management system as outlined in this document will ensure that crops can continue to reach high levels of productivity in the fields in question.

A case study carried out in England (ref. Orson and Harris, 1997) has identified that the development of resistance can be categorized into stages, with each stage requiring a new intensity of management. These management levels naturally carry a cost over what is considered as the standard farming practice. An example is the option of delayed sowing.

Whilst this is a very effective tool for managing weed numbers, the cost of doing so – if yield is reduced – can be significant.

The potential increase in costs associated with resistance management must be weighed against the consequences of not implementing these measures. In severe cases, the rapid spread of uncontrollable weeds can significantly reduce crop yields for a long period and may even affect land value. Accurately assessing the cost of resistance management requires consideration of multiple variables, including crop yield potential, commodity prices, local costs of techniques such as ploughing, weed species, soil type and more. Because these factors vary widely, cost evaluations are only reliable at the local level. While insights from other regions may offer general principles, they cannot provide precise guidance.

Conclusions

The rate at which the resistant weed species will revert to “natural levels” within the population, if at all, will depend on several factors. These include the relative fitness of resistant versus susceptible biotypes, the weed’s germination pattern and its reproductive characteristics. Key genetic and biological aspects such as the resistance mechanism, pollination system, seed production per season, and seed bank longevity all play a role in how resistance persists or declines over time.

Effective management and/or prevention of herbicide resistance can only be achieved through the development and implementation of an Integrated Weed Management program. This approach must incorporate as broad a range of weed control practices as is economically feasible, ensuring a diversified and sustainable strategy.

Steps towards the management of herbicide resistance:

- Assessment of risk through a cropping system checklist

- Evaluation of options (including costs) to be adapted to local conditions

- Implementation of a sustainable weed control program

- Rotation of crops to enable a variety of weed control options

- Rotation of cultural practices to lower the reliance on herbicides

- Rotation of herbicide site of action to reduce the likelihood of resistance to a specific product group

Further Information

Crop Life International

143 Avenue Louise

1050 Brussels, Belgium

croplife@croplife.org

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Guideline to the Management of Herbicide Resistance

Download File (0.3MB)Integrated Weed Management Video

Download File (11.8MB)